Indonesias Asean chair, continuity with prickly tweaks

Date:

11 January 2023Category:

OpinionsTopics:

-Share Article:

Print Article:

By Mr Kavi Chongkittavorn, Senior Communications Advisor: After the democratic transformation in the post-Suharto era in the past 25 years, whenever Indonesia has served as the Asean chair, new ideas and plans seem to mushroom. The Asean Charter and Asean Outlook on the Indo-Pacific (AOIP) were the latest examples of the way in which Indonesia, the world’s third democracy, wanted to shape the future of the regional organization, of which Jakarta is one of the founding fathers.

In terms of the Asean-led principles and guidelines, Asean, under the helm of Indonesia, will as in the past, aim at improving the organization’s effectiveness and dynamism in managing its own affairs as well as external relations with all great powers. However, this time around, the new chair is facing new challenges caused by seismic shifts in geopolitics and geo-economics from within and abroad.

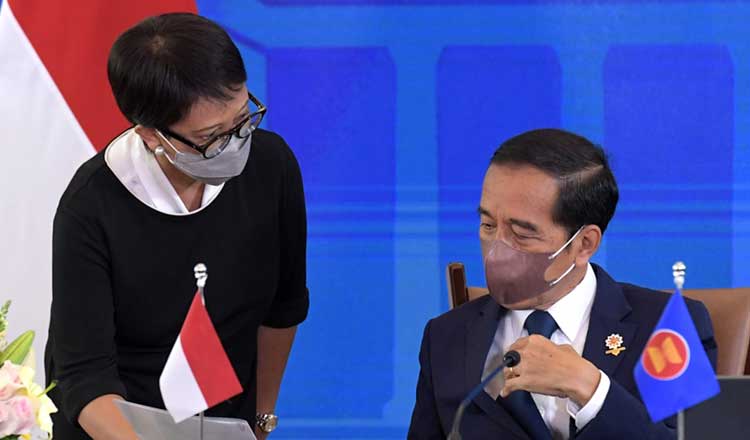

During the handover ceremony in Phnom Penh in November, 2022, Indonesian President Widodo Joko made it crystal clear that under his tutelage, he would promote the bloc’s relevancy and maintain Southeast Asia’s position as the hub of economic growth. That explains why Jakarta has come up with the theme ”Asean Matters: Epicentrum of Growth.” Jakarta carefully selected the word “Epicentrum” to highlight the quintessential role of Asean, which the chair will initiate and undertake for the rest of the year.

To pick up where the predecessor left off, the incoming chair has to manage a whole gamut of Asean cooperation in all three pillars—political/security, economic and social/culture, not to mention the nitty-gritty stuff that has made Asean what it is today. In the post-pandemic era, Asean needs stronger cooperation and commitment to recover from the negative economic impacts and increase the bloc’s resilience to counter whatever shocks come their way in the future.

At the scheduled Asean retreat scheduled for 3-4 February at the headquarters of Asean Secretariat, Indonesia will outline the Asean agenda and priorities and what it sees are the deliverables by the end of this year. Fresh from the success of the G20, President Widodo Joko’s stature has gone up several notches. As such, Indonesia’s new global profile cannot afford to allow the Asean chair to be benign and non-productive. Some observations can be made beforehand as what the new chair has in store.

As is well known, the chair’s priorities can be identified as regional health and food security, energy transition, and digital transformation, all of which were highlighted throughout last year. Given the size of Indonesia and its population and the new planned capital, Nusantara’s continued economic progress and non-disruptive production chains will be essential. Furthermore, today Asean is a non-threatening political and economic space, welcoming all development partners. Such a status quo must be maintained even if the competition among contesting powers will intensify by many folds.

Of late, Indonesia has been bold in proposing new ideas at the High-Level Task Force for the Asean Post 2025 vision. In the meeting in Kuala Lumpur in September, Jakarta proposed to change the way the Asean leaders make decisions based on consensus to a majority vote of at least seven members. The idea caused quite a stir among the senior officials drafting the vision. There will be more proposals coming along as the consultative process continues.

For President Widodo Joko, popularly known as Jokowi, the optics and stakes are high as the public this year will also be zeroing in on one important issue— who will succeed him in the 2024 presidential election? Contending parties will begin to search for presidential candidates for next year’s campaign. Therefore, Indonesia has to walk a tightrope to underline his continued leadership and maintain his political legacy vis-a-vis other matters that might rear their ugly heads.

Beyond the inter-Asean related issues, and just as it did the outgoing chairs Brunei Darussalam and Cambodia, various integrational issues such as the Myanmar Crisis, the South China Sea Conflict, Ukraine, Korean Peninsula, among others will also be discussed. But the quagmire in Myanmar will continue to haunt the incoming chair like a vampire. Given its geographical distance from the hotspot and its previous strong positions against the military junta in Nay Pyi Taw, Jakarta will certainly adopt a more moderate position on the issue now that the country occupies the chair. It does not mean that Indonesia will shy away from further engagement, but it will tackle the Myanmar crisis with prudence—and in a different way from the previous two chairs. For instance, Jokowi will not visit Myanmar and meet with the junta leaders under any circumstances unless there is “substantial progress” in the implementation of the Asean Five-Point Consensus (5PC).

For the past two years, Asean has been seeking to enforce its 5PC, which was agreed in April 2021. At that time, the bloc’s top priorities were on an immediate ceasefire and delivery of necessary humanitarian assistance. For the time being, these two objectives have made little progress due to the ongoing fighting in various parts of Myanmar, especially in the Sagaing and Kayah states. Overall, the war between the military junta and the resistance forces including the People’s Defence Forces (PDF) has intensified and so have the civilian casualties. Lest we forget, fighting among ethnic groups and with the central government has been ongoing since Myanmar’s independence. Unless these stakeholders express the readiness to sit down at a negotiating table, it would be difficult for the Asean process to proceed. They must hold a dialogue among themselves and their common future.

As such, there could be some refocusing of the 5PC to kick off an inclusive political dialogue, instead of treating the conflicts among various stakeholders as a zero-sum game. Indonesia hopes to seek indirect or direct engagement with every conflicting party. During the Asean summit, the leaders agreed that new approaches should be explored to resolve Myanmar’s crisis. At the moment, the high level of civilian casualties is not promising. According to the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners (AAPP), to date, the regime has killed a total of 2,273 civilians and arrested more than 15,400.

Truth be told, civilian casualties are also caused by the People’s Defence Force, Ethnic Armed Organizations, and local militia groups, but no organizations have kept any record. At all the past meetings between the Asean special envoys and the military junta, officially known as State Administrative Council (SAC), this issue has been raised. Due to the junta’s continued violence and brutality against its own people, no one is willing to listen. Recently, the UN Security Council adopted a resolution to condemn the regime in Nay Pyi Taw and called on the SAC to end the violence and release all political prisoners.

Whatever Jakarta plans to do about Myanmar, it will need assistance from member countries that have been directly affected by the conflict. Thailand and Malaysia immediately come to mind. Thailand shares a common border of 2,401 kilometers with Myanmar, which has not yet been demarcated. Thai authorities are nervous every time there are clashes among the numerous ethnic groups, both among themselves and against Nay Pyi Taw, fearing an influx of villagers fleeing conflict across the Thai border. Each day a few hundred villagers from Myanmar are smuggled through natural channels at various places. Local residents fleeing from Myanmar’s North and Northwest regions are congregating along the Thai-Myanmar border. Thailand has to catch up with the situation inside Myanmar and listen to the horse’s mouth. At the February retreat, Bangkok will report the outcome of the Dec 22 meeting for further deliberation.

Malaysia is another country as far as the Myanmar crisis is concerned. More than 300,000 people from Myanmar are living in Malaysia, especially a large group of Muslim Rohingya, who have been discriminated against in Myanmar. During the dry season, hundreds of these refugees flee Myanmar and Bangladesh and risk their lives on the high seas to reach Malaysia.

Ways must be found to jumpstart inclusive political dialogues, especially issues concerning the upcoming election planned for August. If the poll proceeds as planned, the outcome would not be recognized by the region and the international community. The junta cited electoral irregularity in November 2020 as one of the reasons to seize power. It would take a collective decision to decide on the electoral process in order to gain recognition.

Therefore, from Jakarta’s perspective, the priority is to get all stakeholders together to begin a dialogue on issues of concern, which could open ended in the beginning. After all, at the moment, the conflicting partners are using weapons to communicate with one another. To move them to a negotiating table would require both goodwill and good faith by all concerned. For Asean, dialogue partners are as important as ever. For any future ceasefire and humanitarian assistance to be effective and sustainable, their cooperation is indispensable.

It remains to be seen how the chair would like to approach the Myanmar crisis. The onus is on Indonesia as to whether the bloc, under the leadership of the biggest and most powerful Asean member, can make a breakthrough.

This opinion piece was written by ERIA's Senior Communications Advisor, Mr Kavi Chongkittavorn, and has been published in Khmer Times. Click here to subscribe to the monthly newsletter.

Disclaimer: The views expressed are purely those of the authors and may not in any circumstances be regarded as stating an official position of the Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia.